artists:

Wojciech Bąkowski, Tymek Borowski, Olaf Brzeski, Cipedrapskuad, Oskar Dawicki, Mikołaj Długosz, Grzegorz Drozd, Michał Frydrych, Piotr Grabowski, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Mariusz Libel, Jacek Markiewicz, Tomasz Mróz, Laura Pawela, Marek Raczkowski, Karol Radziszewski, Twożywo, Robert Wałęka, Artur Żmijewski

curator: Stach Szabłowski

The exhibition proposes to redefine the position assigned to an artist within the society as well as the role of art in social life. It constitutes an attempt to revise contemporary concepts related to the relation between art and its audience. It sets out to undermine the thread of understanding between an artist and their viewers, which is actually feebler than it seems. As viewers, we wish to learn about art, to make friends and familiarize ourselves with it. Contemporary artists appear to respond to these expectations, taking a step towards the audience.

The tendency to push artists into the arms of the public is reinforced by the nature of institutional life. Contemporary art is an extremely institutionalised domain. Art is accessible for the public almost exclusively via art galleries, museums or art centres. Following a natural institutional instinct, these venues take it upon themselves to popularise and explain art as well as clear up any misunderstanding that may arise in relation to it. Many of them rely on tax financing. Taxpayers make demands and, understandably, claim the right to satisfaction.

The Crimestory exhibition puts forward the suggestion that this right should sometimes be relinquished. Sometimes it may even be impossible to enforce. The idea that one cannot be on perfectly friendly terms with art underlies the show. Art cannot be fully tamed. Frequently, what is the most important in art dwells not within the space of agreement between an artist and the audience but within the space of disagreement, strangeness and conflict.

Lying in wait behind the curtain of friendly gestures, it is conflict that provides the axis of the exhibition. Conflict between an artist and the public, between an individual and a community, between creative freedom and social norm, between established beliefs or notions and an artwork that questions, criticises and destroys them. This is also the conflict between hermetic languages of art and colloquial language.

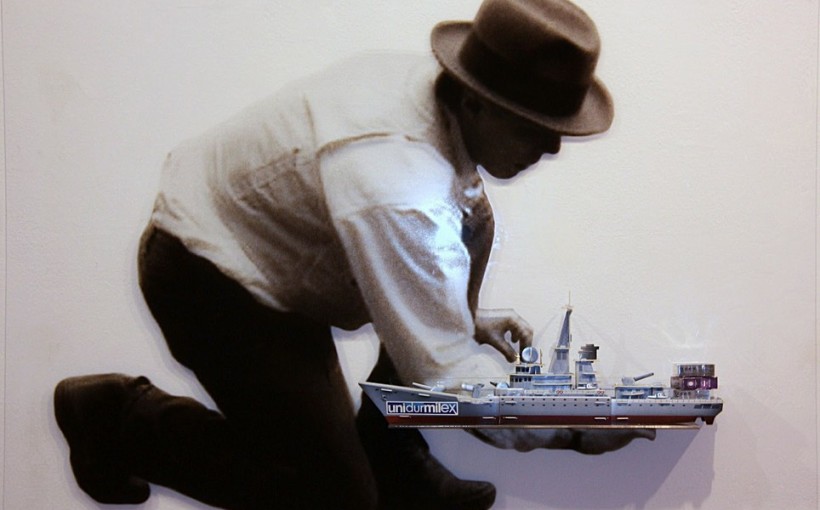

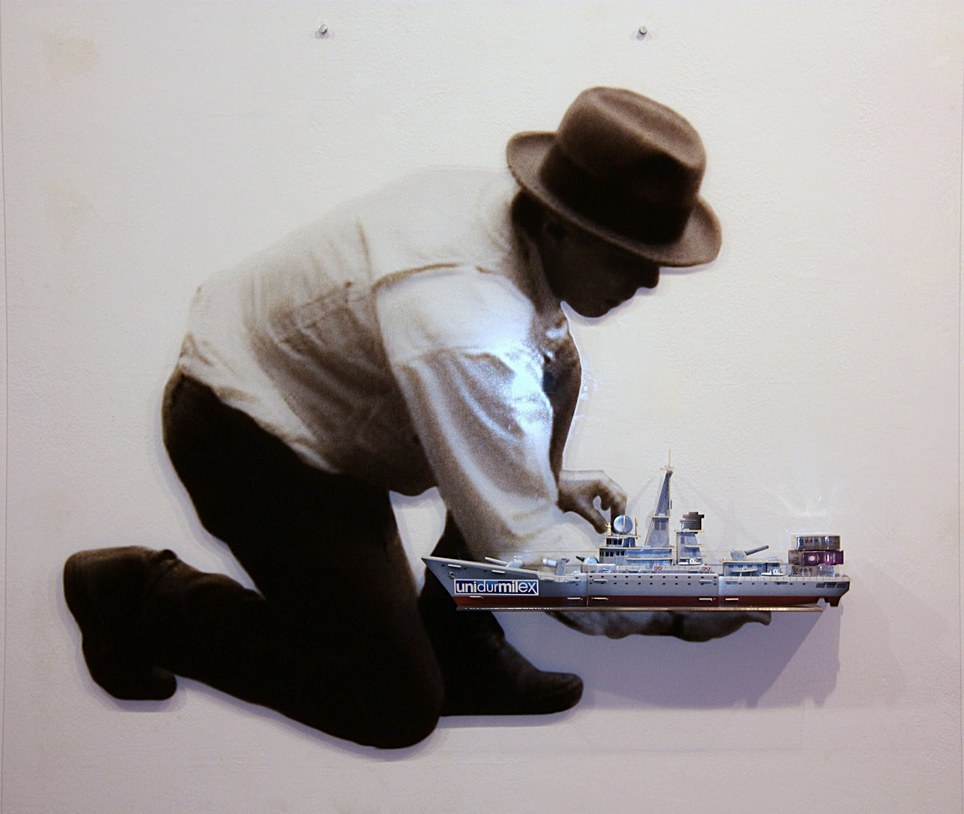

The matter of the Crimestory exhibition is constituted by artworks which may initiate a dispute between art and the public in various fields. Artworks that defend themselves against acceptance. Some of them ostentatiously proclaim the independence of the artist as a creative individual within a community. Others juxtapose the vision of an artist serving the community with another vision – the image of the creator as an outsider, an outcast even, a public enemy, directing criticism at the community. Pieces presented at the exposition include those that give brutal treatment to the viewers’ sensitivity, those that challenge accepted social norms, those that violate political correctness as well as those that question normative morality. The exhibition embraces works whose creators make a transgression at the linguistic level as well as pieces by artists who refuse to communicate with commonly understood codes and make an effort to develop their own language that tends to be hermetic, incomprehensible and full of paradox and untranslatable idioms.

If artworks are the matter of the exhibition, then the asocial (or even, in its extreme form, antisocial) element of the artists’ identities and attitudes – as well as misanthropy, freethinking, arrogance, alienation and loneliness – constitute its spirit. The exhibition is based on the assumption that such attitudes show creative potential.

The issues addressed by Crimestory are universal but we will consider them within the context of the exhibition, in reference to very specific historical and geographical conditions. Crimestory revolves around the case of Polish culture. The historical perspective of the project includes two past decades, or the period after the collapse of an authoritarian regime, an era of free-market democracy, a time when the image of the relation between an artist and their audience is not deformed by pressure coming from an oppressive, totalitarian power. In a nutshell, entering the Crimestory exhibition we are here and now – in contemporary Poland.

The narration of the show unfolds above a crevice between art and the public – a crevice which can turn into an abyss. Institutions as well as curators display a natural instinct telling them to try and fill it in. When it comes to Crimestory, however, our objective is the opposite. Instead of filling it in, we wish to uncover the abyss, to make it apparent and to take a look inside. We believe that the crevice opening between viewers and artists hides something significant – crucial aspects of art, its power to change notions of the world and to emancipate individuals. These aspects can easily be overlooked when art becomes too familiar, too tamed. The exhibition then rests on the assumption that conflict, dispute, even hostility between art and the public can potentially be more creative and inspirational than harmony and mutual understanding. Art can be against us all while being on the side of each and every one of us.

Stach Szabłowski

The Institution is funded from the budget of Toruń Municipality

The Institution is funded from the budget of Toruń Municipality